“Animal welfare is our top priority.”

These words are recited like a refrain whenever someone raises concerns about the use of animals for experimentation, testing or education. Next come assurances that the institution “follows all applicable laws” and that “the work has been reviewed and approved as ethical and humane” by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)—the institution’s federally mandated internal body overseeing its care and use of animals in research, testing, and education. Translation: “The oversight system is working.”

But is it working? How thoroughly was this research reviewed, and how closely were all laws and regulations followed? How much did the IACUC members—most of whom work at the research facility—prioritize animal welfare over practicality or expediency? And what, if anything, happens if laws and regulations aren’t followed?

In December 2022, AWI learned of a disturbing situation involving the use of rats in an undergraduate class at Baylor University. AWI wrote to Baylor expressing grave concerns. Baylor responded—but in an opaque manner that merely raised more questions, so AWI followed up with another letter seeking answers. Many weeks have passed since, with no further response from the university. The situation, described below, serves as a case study illustrating how the oversight system is failing animals and why it must be strengthened.

Institutions such as Baylor that receive federal Public Health Service funding must also comply with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy), with compliance monitored by the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW). In an upcoming issue of the AWI Quarterly, we will present a second case study that examines just how well OLAW “resolves” animal welfare issues.

“It was better for students to not know.”

Baylor’s Learning & Behavior Lab is an undergraduate class, offered for nearly 20 years by the university’s Department of Psychology and Neuroscience. This past fall, approximately 60 rats were trained by students of this class to press a lever and perform a trick. The lab manual indicated that, following this experiment, the animals would be “used by other Baylor researchers for numerous other purposes.” However, as Baylor faculty members reportedly acknowledged, this information was false; in fact, the animals were meant to be killed following their use by the students.

When the truth of the rats’ imminent death came out—after a few teaching assistants came clean to students in their sections—at least one student implored the lab instructor, Dr. Hugh Riley, and the department chair, Dr. Bradley Keele, to have the rats adopted, placed in a sanctuary, or kept as class pets instead. This student, whose plea was denied, told the Baylor Lariat student newspaper that he felt “betrayed” and “duped into a situation where [he was] complicit in killing a life.” When the student asked Riley why students had been deliberately misled, Riley reportedly replied that it was better for students to not know.

Defending the university’s refusal to spare the rats’ lives, Keele—who also chairs Baylor’s IACUC—said that because the IACUC-approved protocol dictated the killing of the rats, the university was bound by law to do so. “We operate 100% to comply with all local, state and federal laws,” Keele told the Lariat. “The euthanasia of the animals in the learning and behavior lab is what we have to do to remain compliant.” This isn’t entirely true—the protocol could be amended to have the rats adopted rather than killed. Regardless, there is an undeniable problem when the oversight system meant to protect animals not only allows the killing of healthy individuals but also is used as an excuse to deny a more humane option.

The failings of Baylor’s IACUC go well beyond approving the senseless killing of so many healthy rats—the use of rats for this class should never have been allowed in the first place. The ethical use of animals in science, including science education, mandates that animals should only be used if the research/learning objectives cannot be achieved using non-animal methods. And in the case of teaching introductory level undergraduate students about operant conditioning, alternatives to live animals do exist and are already in use by this class in the form of “Sniffy the Virtual Rat” software. As stated in the lab manual, “The Sniffy Virtual Rat program is used extensively and often exclusively in many Universities,” and “Using Sniffy also allows for students to observe some learning experiences that a real rat lab could not provide.” Nevertheless, the university has the class follow up with live animals, apparently because, according to the lab manual, use of a real rat in an in-person lab format is “nice.” This attitude inevitably teaches students that rats are expendable—a lesson driven home with force once the students learned of the rats’ fate.

“A little bit of humor here, folks.”

Before the rats were senselessly killed, they suffered senseless deprivations. Per the lab manual, they lived in social isolation, notwithstanding direction from the federal Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, which the IACUC must follow. The guide states, “Social animals should be housed in stable pairs or groups of compatible individuals unless they must be housed alone for experimental reasons or because of social incompatibility.” Social species suffer when deprived of companionship, and here, there is no scientifically justifiable reason for the rats to be housed alone.

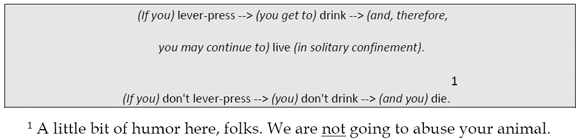

The manual further indicates that the rats were deprived of water for 23 hours a day to motivate them during training to press a lever for a water “reward.” In truth, rats with unrestricted access to food and water readily learn to press a lever for a sweet treat. Thus, had the IACUC done its due diligence, it would have at the very least requested that the animals be housed with a companion and have free access to food and water.

Equally troubling is the manner in which rats are portrayed and belittled throughout the lab manual—for example, as lazy and unintelligent animals for whom solitary confinement in a small cage with little stimulation is not only “reasonable” but also creates a more optimum learning environment. Some of the manual’s statements even make light of the abusive conditions (see screenshot below).

Language matters, particularly in a teaching situation. Educators have a duty to teach young scientists to honor and respect animals used in the name of science.

Following our initial inquiry, Baylor stated, “The IACUC performed a complete de novo review of all protocols involving live rats used for teaching.” It also indicated that it has “re-enacted” an adoption policy as one of several alternatives to killing. Among the questions we attempted to resolve in our follow-up letter: If there was a prior adoption program, why was it abandoned? Will killing remain one of the available options? Will rats continue to be used in this and similar courses—and, if so, will they continue to be subjected to single-housing and prolonged water deprivation? Baylor also stated, “The department revised and corrected the laboratory manual in use in the course to reflect more accurately the policies and procedures of Baylor and the actions and requirements of the IACUC”; however, the university has not responded to our request to see the revised manual.

“Used appropriately.”/“Living the plush life.”

Like most research institutions, Baylor claims high ethical and animal care standards. In September 2022, a puff piece appeared in the Lariat titled, “BSB [Baylor Science Building] Vivarium delves into research with animal welfare in mind.” In this article, Dr. Ryan Stoffel—attending veterinarian, animal program director, and IACUC member—said, “I want to make sure that the animals that we use in research are well cared for and that we take into account their welfare” and asserted that the IACUC makes sure animals “are used appropriately.” Natashia Howard, manager of the BSB director’s office and a former laboratory animal assistant in the BSB Vivarium, claimed, “Research mice and rats get fed very well and are ‘living the plush life.’”

Does the Baylor IACUC really consider social isolation, prolonged water deprivation, and needless killing of rats for an undergraduate psychology course to be examples of animals “used appropriately” and “tak[ing] into account their welfare”? (Meanwhile, the photo accompanying the article shows Stoffel standing in front of a rack full of shoebox cages for mice, barren but for a single cotton Nestlet—an amount known to be insufficient to allow mice to build a nest.)

Baylor told AWI that it has “corresponded with OLAW regarding this instance and has resolved the issues at hand.” And the fact is, Baylor may well have resolved the situation in OLAW’s eyes. IACUCs have a duty to demonstrate good ethics, but have wide discretion and little accountability. Baylor’s treatment of rodents may be highly questionable and even cruel, but it is the type of conduct that is frequently allowed—either because it is permitted under the law or the law is not enforced.

Baylor’s animal welfare record is not unique, nor is it the worst. Institution after institution asserts compliance with the law as proof that its treatment of animals is humane. But the Baylor case amply illustrates that “compliant” and “humane” are not synonymous. Until an oversight system emerges that truly does emphasize animal welfare as the top priority, “compliant” will continue to allow for the misuse and mistreatment of animals in research, testing, and teaching.